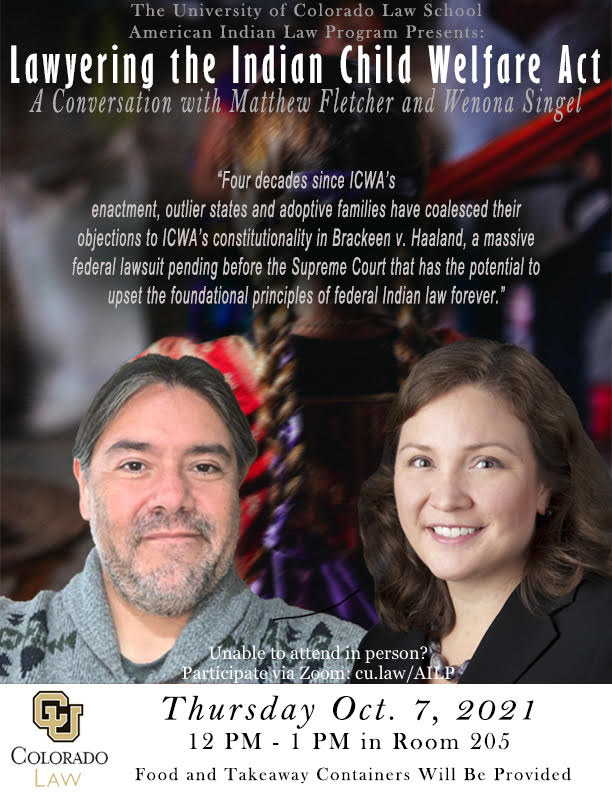

Please join the American Indian Law Program and guest speakers Matthew Fletcher and Wenona Singel for a talk on the Indian Child Welfare Act, the petitions challenging the Act currently pending before the Supreme Court of the United States, and the potential ramifications for American Indians and American Indian law if the Act is ruled unconstitutional. The event will take place on October 7, 2021, from 12:00 PM to 1:00 PM.

To attend via Zoom, please visit cu.law/AILP on Oct. 7, 2021, at 12 PM MT.

Fletcher is the Foundation Professor of Law at Michigan State University College of Law and Director of the Indigenous Law and Policy Center. He is also a member of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. Singel is an Associate Professor of Law at Michigan State University College of Law and the Associate Director of the Indigenous Law & Policy Center. She is a member of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians.

The case Fletcher and Singel will be discussing is Brackeen v. Haaland (formerly Brackeen v. Bernhardt) a lawsuit brought by Texas, Indiana, Louisiana, and individual plaintiffs alleging that the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) is unconstitutional. ICWA is a federal law that provides tribal governments with jurisdiction over custody, foster care, and adoption disputes that involve children residing or domiciled within reservation boundaries and children eligible for enrollment as tribal members. From the perspective of many child welfare advocates, ICWA sets the “gold standard” for maintaining children’s connections to family, culture, and community. But others perceive ICWA as a barrier to their interests in making Indian children available for adoption by non-Indians and to state sovereignty over family law matters.

ICWA (25 USC § 1915) was passed in 1978 to reverse and remedy a long history of federal policy breaking up Native families in the name of assimilating Indians into mainstream society, religion, education, and economies. For decades Indian children were removed, even absent abuse or neglect, because child welfare workers, courts, and agencies believed they would be better off with white parents. However, Congressional testimony showed the opposite; both Indian children and their families were suffering psychological and other trauma as a result of the assimilation and adoption policies.

ICWA created a series of safeguards to prevent the unlawful removal of children from their tribal lands and cultural heritage. For example, when an involuntary custody proceeding is initiated involving an Indian child as defined by statute, notice must now be issued and sent to the child’s parents, the child’s Indian custodian, and agents of each tribe in which the child may be eligible for enrollment. If a child falls under the jurisdictional rules of ICWA, the tribe can maintain jurisdiction over the custody determination and exercise authority to prioritize placement with tribally enrolled relatives or foster care providers in the absence of good cause to the contrary.

Professors Fletcher and Singel, who have authored a book on ICWA and its place in the socio-legal landscape of the United States, will be examining the case and its two overarching questions: 1) whether ICWA is unconstitutionally race-based, and 2) whether Congress exceeded its authority by entering the arena of child placement when it authorized ICWA rather than leaving Indian child placement to determination by the states.

The Brackeen plaintiffs claim that ICWA unconstitutionally discriminates against non-Indian parents seeking to adopt Indian children by focusing on race-matching, preventing the children from finding the best possible home. They say this race-based discrimination should be barred by the equal protection clause of the constitution. However, tribes and Indian advocates assert the long-standing rule that Indian status is political versus race-based and does not violate equal protection. This key distinction is at the heart of many Indian policies, such as those relating to education, housing, and healthcare.

As challenges to the ICWA unfold in the United States, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples provides: “Indigenous peoples have the collective right to live in freedom, peace, and security as distinct peoples and shall not be subjected to any act of genocide or any other act of violence, including forcibly removing children of the group to another group.” In 2021, a study of the United Nations Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples recognized the ICWA as an important measure for advancing Indigenous children’s rights in the U.S.

For additional reading:

Leah Litman and Matthew L.M. Fletcher, The Necessity of the Indian Child Welfare Act (2020)