Photo credit: University of Colorado

On January 23-25, 2024, the University of Colorado hosted an International Expert Group Meeting on “Indigenous Peoples in a Greening Economy,” sponsored by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). The meeting involved experts from the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues and the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; Indigenous scholars; and Indigenous representatives from countries around the world including the United States, Canada, Bolivia, Australia, Nigeria, Kenya, Russia, the Philippines, and Norway, among others. The evening before the meeting, the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) hosted a reception for attendees, highlighting the close collaboration between NARF and the University of Colorado Law School through their joint initiative, The Implementation Project, which works to advance implementation of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

On Tuesday, the Expert Group Meeting opened with a blessing by Ute Mountain Ute tribal chairman Manuel Heart who said,

“It is a huge honor for me represent the Ute people and welcome the Indigenous Peoples from around the world. Today we feel the impact of climate change and we hear and see it all around us throughout the year.”

To address climate change, countries and companies alike are turning to other sources of energy besides fossil fuels—wind, solar, battery. The assumption is that these new forms of energy are “greener” and will benefit all of society. But speakers at the meeting revealed that the transition from fossil fuels to other alternatives poses both opportunities and challenges. On the one hand, some Indigenous Peoples are revitalizing sustainable uses of the environment, as in the traditional use of Acacia trees among the Maasai people and taro farming among Native Hawaiians. In other instances, such as the Yurok Tribe’s participation in carbon emissions trading, green economy innovations have provided revenue that funds the recovery of forests and rivers.

Photo credit: University of Colorado

However, to the extent that new technologies stress extraction of lithium, cobalt, copper, and nickel, they pose the same (or worse) threats to Indigenous Peoples’ lands, waters, plants, and landscapes as more conventional extractive activities. During the event, attorney Jennifer Weddle noted that mineral extraction in the United States threatens Tribes’ sacred places in locations such as Thacker Pass and Oak Flat. Beyond extraction, green technologies like wind turbines disrupt reindeer herding by the Sami in Nordic countries, a point made by Eirik Larsen of the Sami Council.

A concept note by UNDESA explained:

Although Indigenous Peoples account for only around 5 percent of the world’s population, they effectively manage an estimated 20-25 percent of the Earth’s land surface. This land coincides with areas that hold 80 percent of the planet’s biodiversity and about 40 percent of protected areas and ecologically intact landscapes.

Accordingly, Francisco Calí Tsay, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, called for a “human rights framework,” recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ rights to self-determination, land, and culture, to guide all green economy measures. Certain speakers challenged the term “green economy,” associating it with exploitative capitalist structures and values. Indeed, speakers at the UN meeting revealed that these projects often replicate colonial norms and practices that have threatened Indigenous Peoples in the past. At a minimum, participants agreed that great care is needed to ensure that development projects are undertaken with Indigenous Peoples’ free, prior, and informed consent.

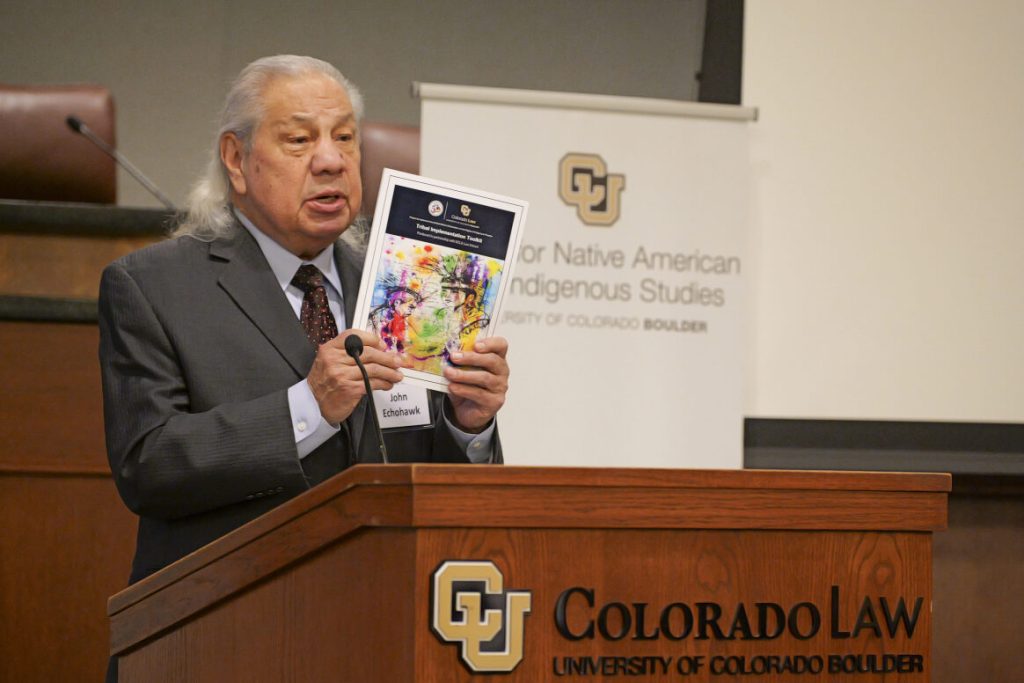

Photo credit: Native American Rights Fund

The gathering also acknowledged the need to address and remedy past and ongoing harms caused by fossil fuels and related industry. In a panel on Indigenous Peoples’ relationship with the environment, President Whitney Gravelle of Bay Mills Indian Community shared an Anishinaabe origin story in which the Great Lakes were created as the “heart” of Turtle Island (North America). She noted that the Line 5 Oil Pipeline, operating illegally in Michigan, poses great risks to drinking water, fishing, hunting, transportation, and commerce in those same Great Lakes. President Gravelle stated,

“The question is not if the pipeline will leak. It has leaked dozens of times over the decades. Line 5 threatens not only the tribes, but anyone and everyone who utilizes the Great Lakes.”

During the meeting, expert panels also addressed themes such as Indigenous Peoples’ participation in the green economy, effects of green entrepreneurship and green enterprise on Indigenous Peoples and their communities, and human rights and corporate responsibility. Speakers noted that new technologies can create incentives to invade and take Indigenous lands and resources. They further established that Indigenous knowledge systems and values are essential to sustainable development. Several speakers expressed concern for “human rights defenders,” the individuals and groups who use their bodies and voices to protect lands, and are often charged with crimes, like trespass, for doing so.

The meeting was focused not just on documenting concerns around the emerging green economies, but also on identifying solutions. The concept note explained that:

A key objective of the expert group meeting was to develop strategic guidance and action-oriented recommendations for States, intergovernmental organizations, private companies, the United Nations system and Indigenous Peoples’ organizations to ensure and protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples in the transition towards a more sustainable economy.

Photo credit: University of Colorado

On the last morning of the meeting, experts and observers engaged in a broad and intense discussion. Among other points, participants emphasized Indigenous Peoples’ own laws, customs, and traditions of care for Mother Earth and called on States to support Indigenous Peoples’ self-determination with respect to participation in the greening economy. UNDESA will issue a report, with specific recommendations, before the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues’ annual session in April 2024, and Indigenous Peoples will be able to use these recommendations in advocacy with States, industry, and others.

Native American Rights Fund Executive Director John Echohawk explained:

“Indigenous Peoples from around the globe are seeing the damage that climate change causes in their communities. This meeting was an opportunity to envision solutions that will help, instead of harm, Tribes, along with their lands, waters, and resources. There is power in coming together to assert Indigenous Peoples’ voices in global dialogues.”